The Kindness of Section 14 & the Cruelty of Redevelopment

Gentle reader,

Late last month, a lawsuit was filed in Palm Springs on behalf of hundreds of Black and Mexican families who were displaced by a 1950s redevelopment scheme to transform their poor, segregated community into a commercial district for vacationers.

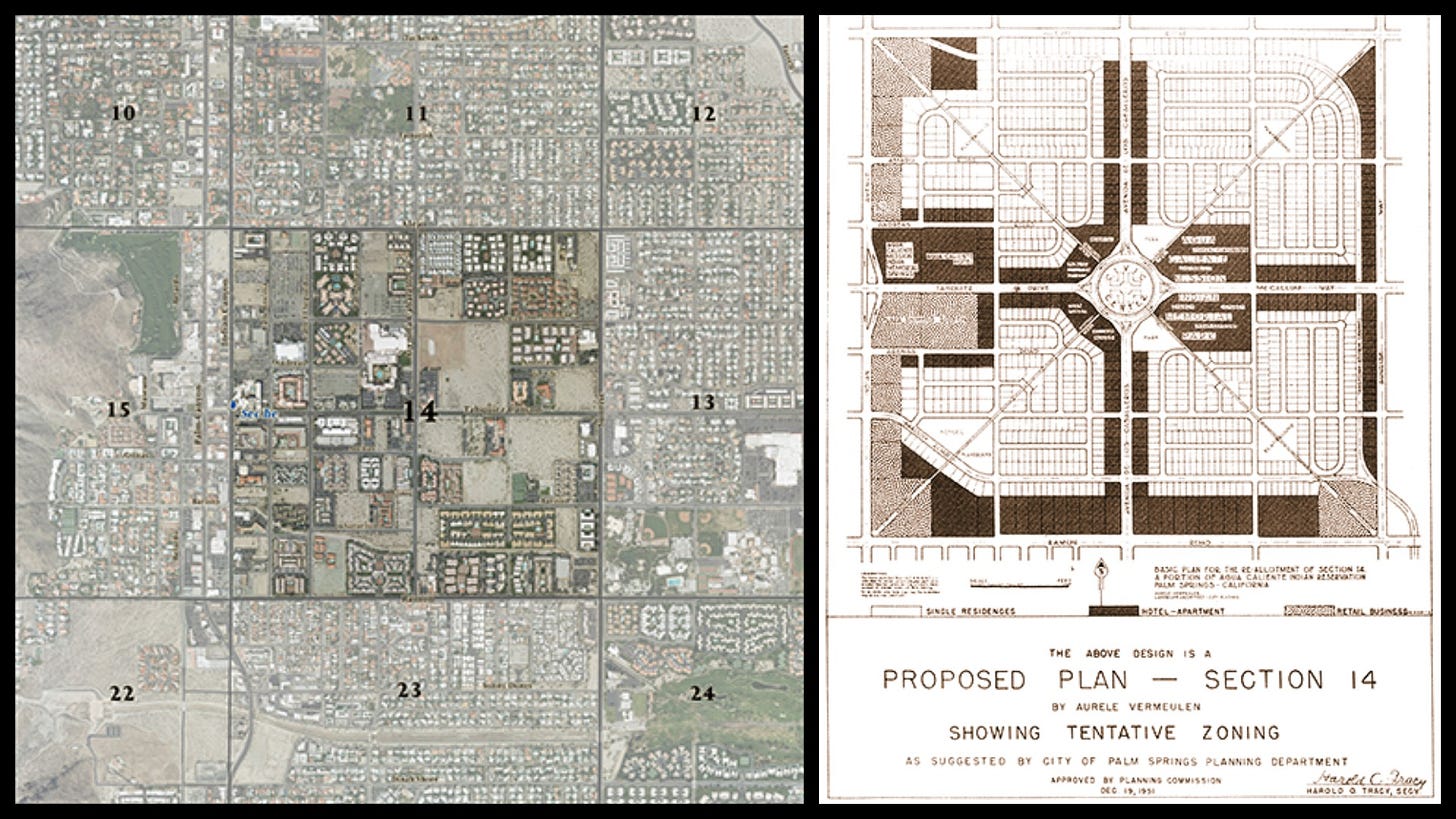

This neighborhood, one square mile called “Section 14” in bland government parlance, was ultimately transformed through demolition and zoning changes into some of the most valuable property in Southern California.

But the cost for the terrorized tenants forcibly evicted and made to watch their homes and possessions torched was enormous. Decades later, their advocates say $4 Billion would be a start in compensating the affected families for their trauma and loss of generational wealth.

When we saw news of the lawsuit, we were reminded of an extraordinary incident that is central to our Eastside Babylon true crime tour.

It was February 1940, and a young Montebello mother was suffering from postpartum psychosis, a disease that was not yet well understood. Betty Hardaker’s delusions were centered around her four-year-old eldest child Geraldine, a beautiful girl upon whom she doted.

The world seemed very cruel and dangerous to Betty, and she wanted to protect her child. She did this in a way that made sense in her disordered mind: Betty murdered Geraldine, as quickly as she knew how, by banging her skull against the bathroom sink at the local park. She left the body, which no longer needed protecting. And then she started walking.

This is where Section 14 comes in. Geraldine’s corpse was found around 4pm, and an all-points bulletin issued for her missing mother. By this time, Betty was fifty miles east, in Colton, hitchhiking aimlessly.

The next morning, Ben Munesa went to Palm Springs police and told them that he and his friend Emil Bostic had dropped the missing woman off at a local hotel. That wasn’t quite true. Betty had been turned away from the hotel because she had no money and no luggage, was dressed inappropriately in riding gear, and muttering to herself.

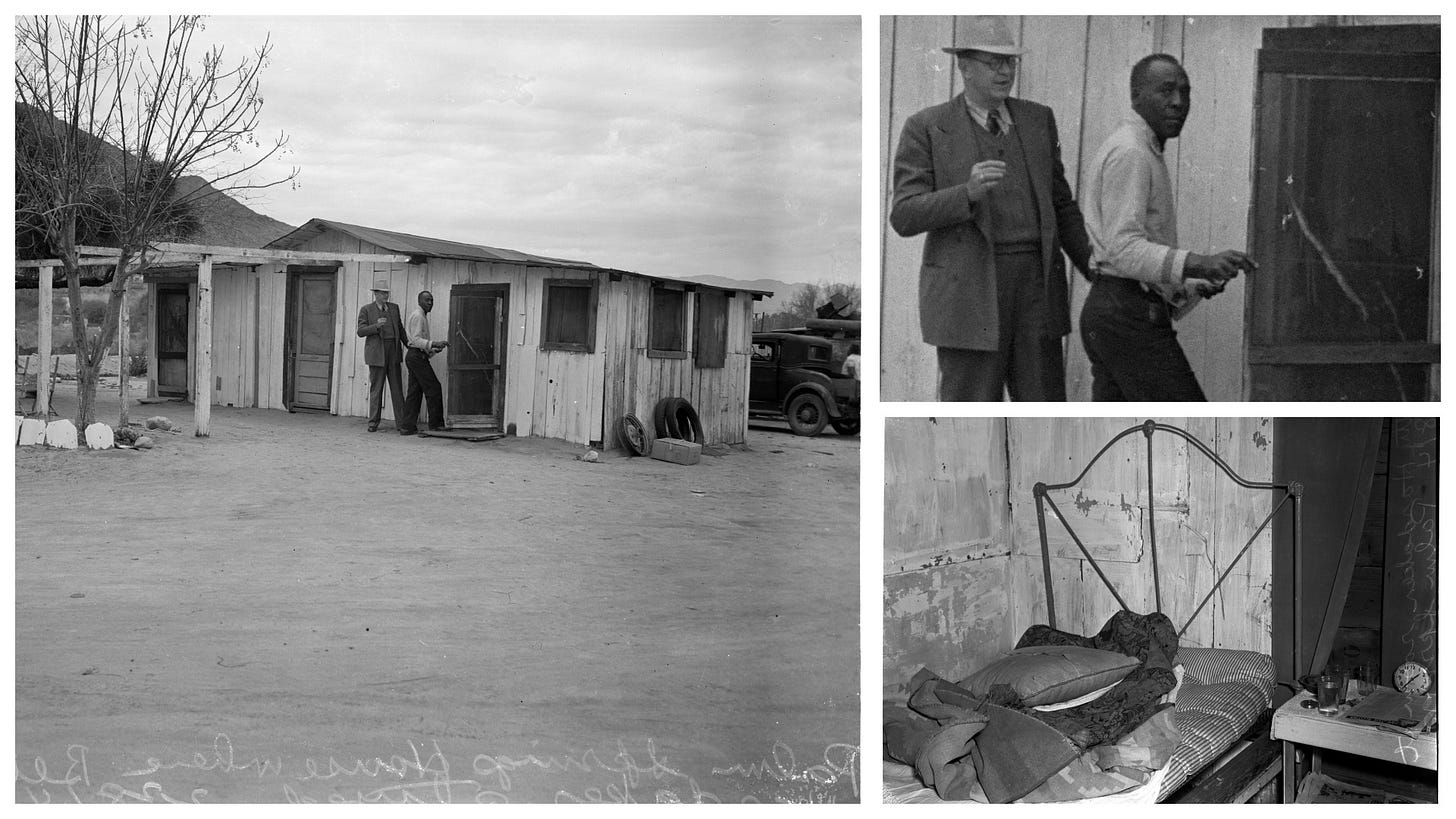

She had actually spent the night in an abandoned shack in Section 14, and Ben and Emil had stayed there, too. They could tell Betty needed a doctor, but as Black men who had been alone—though not, they insisted, intimate—with a white woman, they knew they were at great risk from a racist legal system.

They could have put Betty back into their old Ford and driven her out into the desert and left her there. They could have locked her in the closet and left town. Anyone would have understood why.

But instead, after a couple of hours Ben went back to the police and led them to the shack where Betty was hiding. She was scared and hungry, but glad of the chance to confess her sins and see her family. At trial, she was found insane and sent to a psychiatric hospital. In time, she came home to be a mother to her surviving children.

This story is not a happy one, but were it not for Section 14, it could have been more tragic.

Betty Hardaker was lost and vulnerable, placing herself at great risk by getting into strange cars. Dropped at a hotel, this woman in obvious distress found no compassion. So Ben and Emil took her to land owned by the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians, where the tribe allowed working families banned from Palm Springs’ racially restricted neighborhoods to erect modest dwellings, and where empty shacks were left unlocked for those who needed shelter.

The lessons of how the tribe used their land and supported a community, and how corrupt local government destroyed it all for short term profit, echo through the decades to reach a California where shelter is in short supply, even though it’s all around us. Let’s try to listen.

82 years ago, two people who knew they could find shelter in Section 14 exhibited kindness and bravery that still leaves us awestruck. As the case for mass compensation works its way through the legal system, we’ll be watching with great interest, hoping to learn more about this community where folks were desperately poor, but rich in integrity, and where Geraldine’s stricken mother was protected long enough to find her way back home.

yours for Los Angeles,

Kim & Richard

Esotouric

Psst… If you’d like to support our efforts to be the voice of places worth preserving, we have a tip jar and a subscriber edition of this newsletter, vintage Los Angeles webinars available to stream, in-person walking tours, gift certificates and a souvenir shop you can browse in. Or just share this link with other people who care.

UPCOMING WALKING TOURS

• Saturday, December 17 - Bunker Noir! True Crime on Los Angeles’ Bunker Hill Tour

• Saturday, January 14, 2023 - Human Sacrifice: The Black Dahlia, Elisa Lam, Heidi Planck & Skid Row Slasher Cases

• Sunday, January 29, 2023 - Miracle Mile Marvels & Madness

• Saturday, February 11, 2023 - Broadway: Downtown Los Angeles’ Beautiful, Magical Mess

• Saturday, February 18, 2023 - Evergreen Cemetery, 1877

• Saturday, February 25, 2023 - Westlake Park Time Travel Trip

• Saturday, March 11, 2023 - Downtown Los Angeles is For Book Lovers

Fascinating story! Thanks for the research! I am also waiting to see if the Section 14 victims receive any compensation.