Gentle reader,

This week, Los Angeles City Councilmember Eunisses Hernandez introduced a motion acknowledging that the proposed redevelopment of the Lincoln Heights Jail into a "maker's district" is not actually happening.

Her idea for the massive, derelict property on the Los Angeles River is to recognize it as a stigmatized site and explore demolition options. We think preservation and adaptive reuse is a far better choice, greener, and more respectful of those who came before us. And this building has already been saved from demolition by a community led preservation campaign in 1993!

Because the Lincoln Heights Jail is so much more than a vacant, vandalized shell filled with ugly memories of unjust incarceration. The jail era represents just 34 of the municipal landmark's 92 years (1931-65), eclipsed by significant periods of community service, film location use and illicit access. Even closed to the public, it is a compelling draw.

In April 2023, The Artery ascended to document the present derelict state of the landmark as part of the DRONESCAPE series on significant Los Angeles buildings in peril (see also: Wilshire Professional Building, Morrison Hotel, Los Angeles Historic Theater District). This is an instructive companion piece to Nathan Marsak's Cranky Preservationist visit, shot in August 2017, when redevelopment cash was still lining civic pockets.

It's hard for Angelenos to understand how the Lincoln Heights Jail became a blighted white elephant over the past 13 years, because much of the reporting appeared in the now defunct hyper-local, bilingual Eastern Group Publications newspapers (1945-2018). It's a troubling tale of political machinations, community disenfranchisement and failed civic stewardship that needs to be told, so that stakeholders understand how they’ve been screwed and why this place matters.

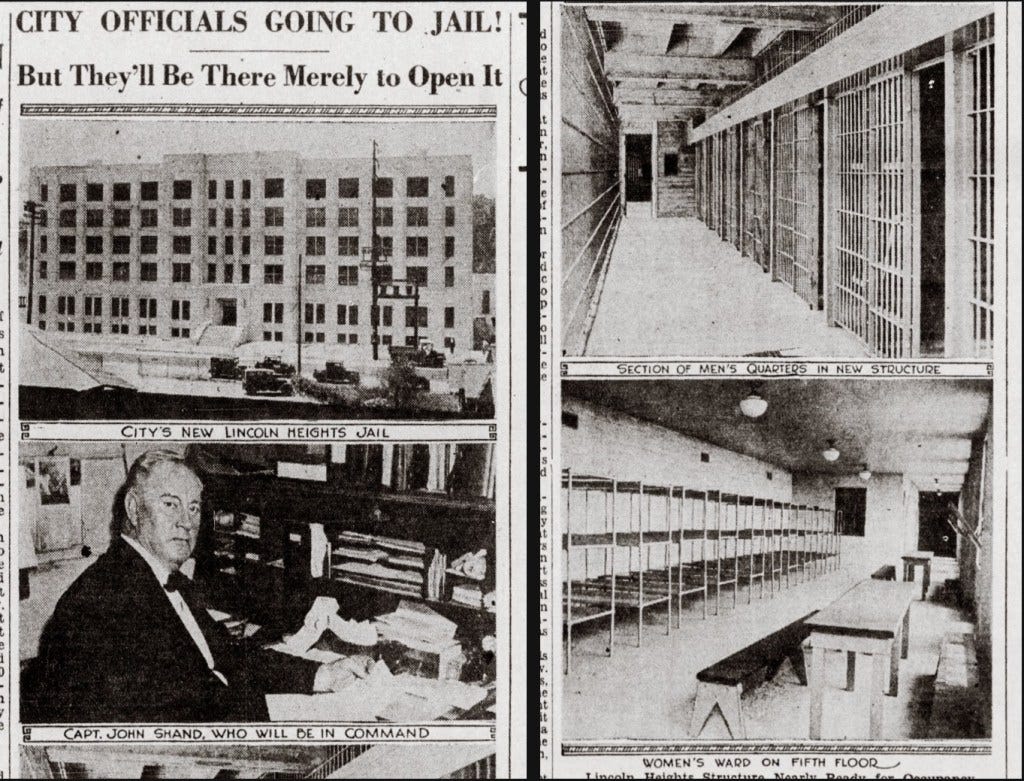

The "new" Lincoln Heights Jail was in service from August 1931 through June 1965, then briefly reopened during the Watts Rebellion, after which the County took over municipal jailing. The original building, packed well over capacity of 625 prisoners, was expanded in 1949 to accommodate up to 4000 inmates (four to a cell). The Los Angeles City Construction Department designed the 1931 jail, and master architects Gordon B. Kaufmann and Jesse E. Stanton the addition.

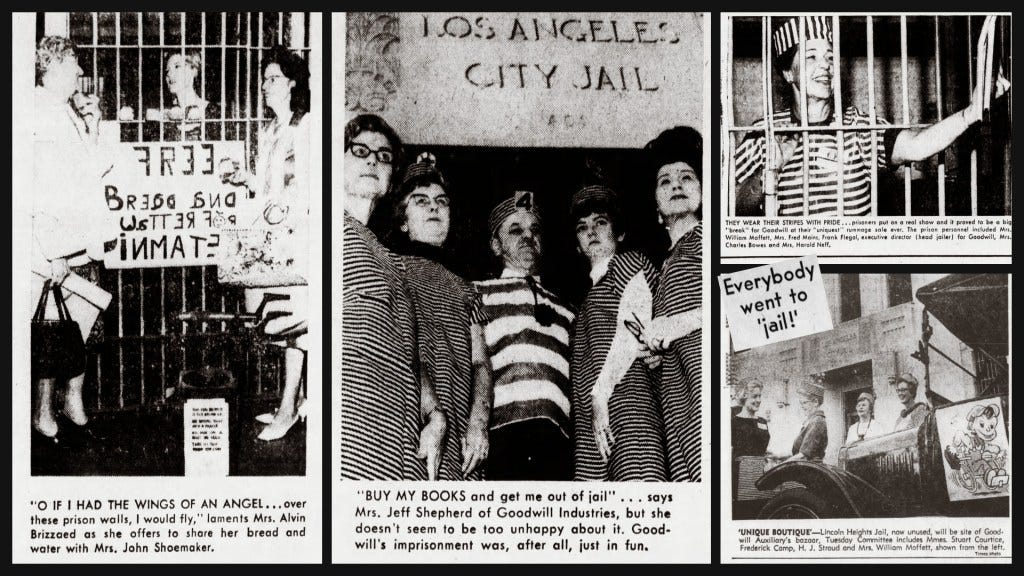

A few years after the jail closed in 1965, a sausage maker rented the industrial kitchen. Neighbors included the Frisco sourdough baking company (makers of Musso & Frank's table bread), Goodwill Industries and Lawry's California Center.

The Women's Auxiliary of Goodwill used the jail for their quirky 1966 fund-raising bazaar, Unique Boutique, and Hollywood costumes and memorabilia moldered in the cells (see the Biography section here). The Long Goodbye, Caged Heat, A Nightmare on Elm Street and L.A. Confidential were all shot within.

But mostly, the huge building sat empty, too expensive to demolish, too purpose-built to appeal to commercial tenants. Gradually, affordable space was offered to community groups, location scouts discovered it, and the old jail became something new.

In 1977, the fifth floor was converted into the Los Angeles Youth Athletic Club (L.A.Y.A.C.), funded with a $300,000 Community Block Grant and administered by Rec and Parks; it would become an important boxing training ground. Around 1980, Bilingual Foundation of the Arts (BFA) converted the old courtroom into a 99-seat theater, occupying the west side basement and first floor. Councilman Art Snyder had a field office there, and LAPD used the basement washing machines. Space was also granted to Project HEAVY (Human Efforts Aimed at Vitalizing Youth) and the Youth Training and Employment Project.

Then there was Aztlán Cultural Arts Foundation (1991-1999), which executive director Armando Martinez recently described as transforming "a place of oppression to a place of liberation." An example of this alchemy was Salvador Anguiano Sandoval's one-man show in 1999; the 73-year-old was a 1940s gang member who'd served time inside the walls that now held his paintings. ACAF’s rent for the east side of the basement and first floor with access to the courtyard was a symbolic $1/year, which co-founder Leo Limón suggested was due in part to having gone to junior high with Councilmember Mike Hernandez.

In 1994, when Metro prepared an EIR for the proposed Burbank-Glendale-Los Angeles Rail Transit Project, special attention was paid to Lincoln Heights Jail, and it was spared demolition for new tracks.

It didn't hurt that the year before, a coalition of community and preservation groups, including the Los Angeles Conservancy and Los Angeles Police Historical Society, had successfully advocated for the city owned jail to become protected landmark (Historic-Cultural Monument #587).

That's why we were able to take a group through the gym and into the old cell block in September 2009, on the debut edition of John Buntin's L.A. Noir tour. But when the tour rolled around again in April 2010, our friends at the gym were gone!

So what the hell happened? The cynical answer is that racketeers took over City Hall, and seized control of all civic real estate assets that they thought they could flip to their developer buddies and connected non-profits. In the case of Lincoln Heights Jail, the unfortunate result is that whatever deals were planned fell apart, and that's been just tough luck for the neighborhood and the landmark and the taxpayers who paid for the L.A.Y.A.C. boxing gym.

And because Lincoln Heights Jail was city owned, with tenants enjoying reduced rent due to political patronage, there was no recourse in 2010, when then councilmember Ed P. Reyes used questionable fire inspections to evict L.A.Y.A.C. with no suitable replacement gym.

At the time, Reyes said the plan was to hand control of the building over to the city's own newly formed Los Angeles River Revitalization Corporation (LARRC) non-profit, use Prop K funds to build the third biggest rock climbing wall West of the Mississippi, invite BFA to return and use the jail as a cornerstone of riverfront revitalization. But none of this happened. Instead, the jail has been mostly empty and decaying ever since.

(Parenthetically, Scott Johnson at the Mayor Sam blog dug into the issue in 2010, and cast blame on Jose Huizar, Ed P. Reyes, Antonio Villaraigosa, USC and Lincoln Heights Neighborhood Council. More light is shone by scouring the 2012 case file, where citizen activist Joyce Dillard objects to the illegal hand off of public property to tenants including Homeboy Industries and and Lauren Bon's Metabolic Studio.)

The city is a terrible steward of old buildings. In 2000 when EIDC, the scandal-plagued predecessor of FILML.A., was exploring a long-term sweetheart $1/year lease—"fun" fact: EIDC spokesman Morrie Goldman is a cooperating witness in the Jose Huizar public corruption case— a report estimated there was $1 Million in deferred maintenance, and that it would cost $10-15 Million to renovate.

Yet once the tenants were gone in 2010, all General Services had to do was secure the site. Instead, as the councilmember and his pals played real life SimCity, the property was left open so that urban explorers, vandals, metal thieves and ghost hunters could strip, tag, deface and encourage others to break in. It's been a sickening free-for-all.

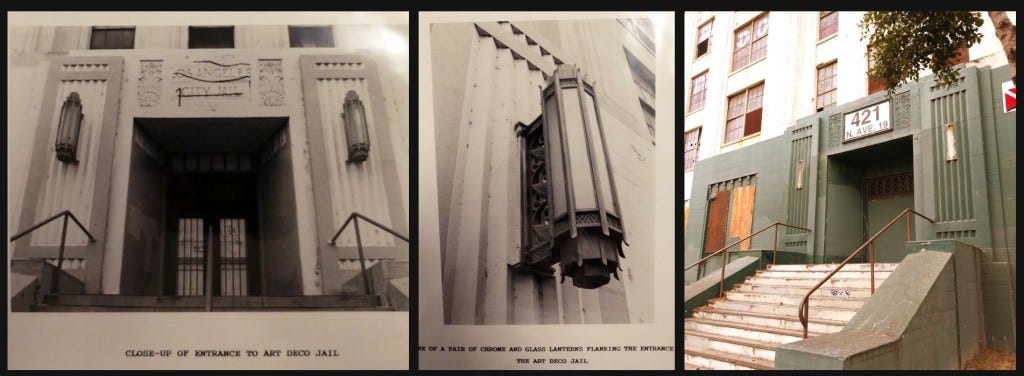

Who're you gonna call when, sometime between July 2016 and January 2017, the iconic art deco lanterns that were prominently featured in the 1993 landmark nomination vanished? Like so much else that's wrong with Los Angeles, it is the city's fault.

There were whispers that the empty jail was again threatened by rail expansion, high-speed this time. When the rail scheme sputtered out in 2017, then councilmember Gil Cedillo—who was routed by Hernandez, then refused to resign when caught on tape scheming to disenfranchise voters—and his City Hall cronies controversially selected two politically connected developers to transform the site into a mixed use development. (The community's clear choice was the losing "Las Alturas" proposal from WORKS and Omgivning.)

But Lincoln Property Company and Fifteen Group (of Wyvernwood infamy) never turned a spade of dirt. Instead, they squatted on the deal, balked at remediation costs, paid lobbyists, and failed to meet contractual deadlines. The city gave them additional time in February 2020 and in May 2022, but according to Councilmember Hernandez' motion, they backed out with no public notice late last year.

Like Los Angeles itself, the Lincoln Heights Jail has a complicated history, representing a painful legacy of racially charged, homophobic and anti-poor policing. This ugly past won't cease to exist if the building is demolished any more than Jose Huizar's and Gil Cedillo's corrupt demolition of Parker Center changed anything about the LAPD. But if demolished, it will become harder to tell the stories of the people who suffered and sought justice in the Lincoln Heights Jail.

The building is so much more than just the bricks that were spattered during the horrific Bloody Christmas assaults and the cages that imprisoned Angelenos guilty of nothing more than cross-dressing. It hasn't been a prison longer than it ever was one. And the site represents an early victory in community opposition to urban prisons, with a proposal to sell it to the state quashed in 1974.

In 1993, when the Lincoln Heights Neighborhood and Preservation Assn. applied for landmark status to protect the jail from Metro, member Michael Diaz addressed the site's complicated history: "I think we have to look at buildings not only for the past, but also for the future. Aside from its historical aspects, this building has proven to help the community socially in its adaptive reuse with the theater and the gym."

He's right. But that future was stolen when Ed P. Reyes kicked everyone out in 2010, and we can never get back those lost years. What we can do is give the Lincoln Heights Jail a chance to be of service once again.

If you agree that the jail is worth preserving, because it's an historic landmark, because it's a greener solution than demolition, because it's a place you want to visit, because it's already been saved once, please let Councilmember Eunisses Hernandez know that you want to see the city pursue adaptive reuse options, and not demolition. In addition to calling or emailing the council office, you can click "NEW" and submit a written public comment for the case file.

We'll update our blog with news about the Lincoln Heights Jail proposal, so watch this space!

yours for Los Angeles,

Kim & Richard

Esotouric

Psst… If you’d like to support our efforts to be the voice of places worth preserving, we have a tip jar and a subscriber edition of this newsletter, vintage Los Angeles webinars available to stream, in-person tours and a souvenir shop you can browse in. Or just share this link with other people who care.

UPCOMING BUS & WALKING TOURS

Evergreen Cemetery, 1877 (Sat. 5/27) • Highland Park Arroyo Walk (Sat. 6/10) • Bunker Hill’s Modernist Marvels with Nathan Marsak Walk (Sat. 6/17) • The Real Black Dahlia Bus Tour (Sat. 6/24) • Echo Park Book of the Dead Bus Tour (Sat. 7/1) • New! The Run: Gay Downtown History Walk (Sat. 7/8) •Westlake Park Walk (Sat. 7/15) • Raymond Chandler’s Los Angeles Bus Tour (Sat. 7/22) • Angelino Heights & Carroll Avenue Walk (Sat. 8/5) • Charles Bukowski’s Los Angeles Bus Tour (Sat. 8/12)

Share this post